One of the benefits of a long career across a variety of enterprise companies is that I have seen a variety of solutions to getting stuff done. This post will mainly be about operational cadence work and incident response. The related problems of developing new software solutions are a different and honestly more familiar problem. Approving, releasing, selling, and monitoring that software is the set of solution patterns we’ll look at here.

Some patterns are more effective than others, but there are requirements: all teams cannot use all methods. Said differently, the correct process tool for a given team is dependent on the size of the problem as well as the type of the problem. One Size Fits All is not an option in these solutions.

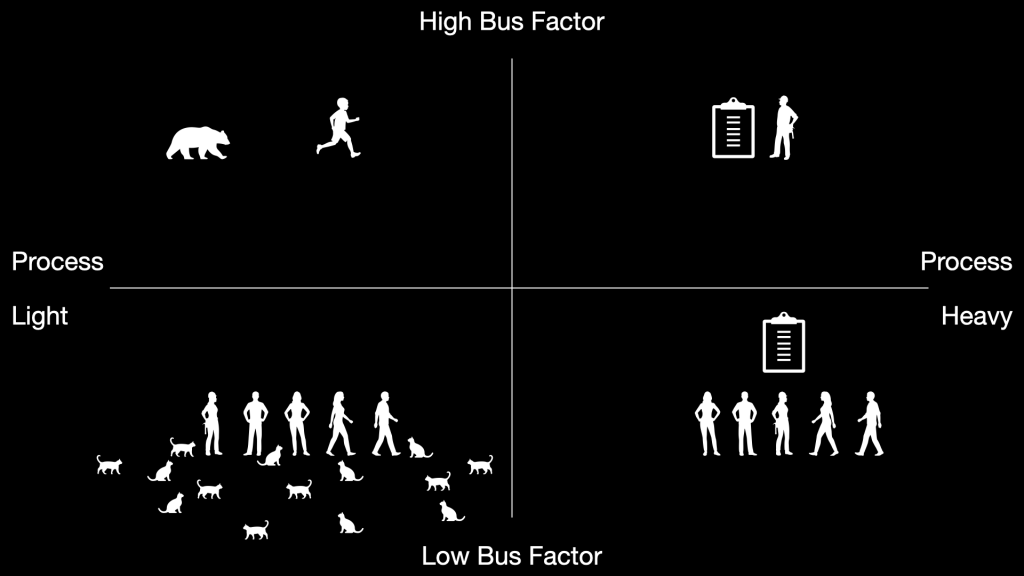

Let’s do a quadrant:

- Horizontal Access: Process Heavy or Process Light.

- Vertical Access: High or Low Bus Factor.

And quickly look at the outcomes:

- High Bus Factor, Low Process: One person does everything, using memory and luck. They are staying ahead of the bear almost all of the time. They do releases and troubleshoot outages from home when they’re sick, and they haven’t taken an unplugged vacation in years.

- High Bus Factor, High Process: One person does everything, using a documented process and checklist. It’s theoretically possible for this person to have a life outside of work, because someone else could do the needful for them. Of course, that is only true if it’s tested from time to time, otherwise the backup will find that second person doesn’t have access to systems and steps six through ten have been reworked because that vendor was replaced… this section of the quadrant may be more theoretical than practical.

- Low Bus Factor, Low Process: Lots of people could do all the things but it’s unclear how those things are being done. It’s a team effort do-acracy! Cat herding is the outcome, and if it is successful it’s probably because one or two people are actually doing most of the work while everyone else… doesn’t.

- Low Bus Factor, High Process: Lots of people can do all the things, using a documented process and checklist with ownership. Someone might be a formal coordinator, or maybe a glue worker helps here. There might even be a RACI matrix involved.

If your entire team is three people and a dog, then your team’s bus factor is very high (especially in San Francisco). There simply isn’t enough time to keep everyone involved in everything. Your process doesn’t have to be low, but you’re also not getting a massive benefit from process. Documented process, if accurate, is just providing some coverage for when the infrastructure hero is sick. On the other hand, with a larger team the lack of process becomes a real hindrance. In a large team some amount of churn is a given: people’s lives and career goals change, the organizational needs change, and people shift in and out of the team accordingly. New team members and ideas about what’s necessary come and go. In this larger sort of team process is what keeps the organization’s institutional memory intact.

Switching from one type of structure to another is a challenge because all change is at least a little hard, but the bigger barrier by far is organizational willingness to accept growth and adopt process. You can add more people to chaos without decreasing the chaos at all. In fact, moving from high bus factor to low bus factor without changing the amount of process is a fairly normal operation. It’s really simple to add another project, hire some more people, complain that everything’s a mess, and praise the heroes who keep pulling dinner out of the fire. Now there’s more chaos, and more heroes are needed, it’s so great that we all work so hard!

Increasing process on the other hand… feels like slowing down. The type of people who found companies might not always take kindly to glue people with flowcharts, checklists, and process gates. That’s by no means a blanket statement: I’ve worked with founders who are quite aware of the value in solid operational process. I’ve also known founders who are less willing to condone a dedicated focus on operational excellence. When in a very small team, that’s tough to argue with since the value of adding some process is difficult to recognize.

The challenge is that at each step of growth, adding a new process may still appear to be unnecessary, since you’ve gotten by so far without it. Failures of operational process look like failures of individuals: maybe some people get disciplined or fired, but of course that solved everything and there’s no need to change anything fundamental, right? Especially in a zeitgeist of downturn, it takes a mature and bold founder to accept that there is value in looking at how things are done. That doesn’t have to happen when the organization is very small, but if it hasn’t happened by the time it gets very big, it’s next to impossible to retrofit.

See also: